Sunday, 13 November 2011

Explaining El Nino and La Nina

Amazon fire season 'linked to ocean temperature'

Continue reading the main story

The team developed a model that offers a fire season forecast up to five months in advance

The team developed a model that offers a fire season forecast up to five months in advance

Sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies can help predict the severity of Amazon fire seasons, a study has suggested.

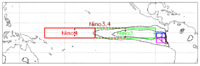

A team of US scientists found there was a correlation between El Nino patterns in the Pacific and fire activity in the eastern Amazon.

Writing in the journal Science, they say they also found a link between Atlantic SST changes and fires in southern areas of South America.

They said the data could help produce forecasts of forthcoming fire seasons.

"We found that the Oceanic Nino Index (ONI) was correlated with interannual fire activity in the eastern Amazon, whereas the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) index was more closely linked with fires in the southern and south-western Amazon," they wrote.

The ONI is a system used to identify El Nino (warm) and La Nina (cool) events in the Pacific Ocean, while the AMO index performs a similiar function in the Atlantic.

'Early warning'

"Combining these two indices, we developed an empirical model to forecast regional fire severity with lead times of three to five months," they explained.

"Our approach may contribute to the development of an early warning system for anticipating the vulnerability of Amazon forests to fires."

Previous studies have shown "high-fire" years in South America are generally associated with an extended dry season and low levels of rainfall.

It has also been shown that variations in precipitation levels in the Amazon is regulated by SSTs in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

"The most severe droughts observed in the Amazon over the past three decades have occurred when the tropical eastern Pacific and North Atlantic were anomalously warm," they said.

A reliable early warning system would be a key tool for relevant bodies and agencies to focus policies and resources effectively, observed the researchers, drawn from a number of US institutes.

"Managing fires to conserve biodiversity and carbon stocks in forest and savannah ecosystems requires advance planning on multiple timescales," they said.

These include "design of policy mechanisms that modify long-term development, as well as improved use of short-term meterorological forecasts of fire behaviour during years with high fire season severity."